The grandmother of Europe and her legacy

Sick princes bleed to an early death

Cases of haemophilia became more frequent in Europe’s ruling dynasties from the 19th century onwards. The spectacular phenomenon has since inspired various myths. Let’s take a deeper look into the events.

Text: Tobias Hamann

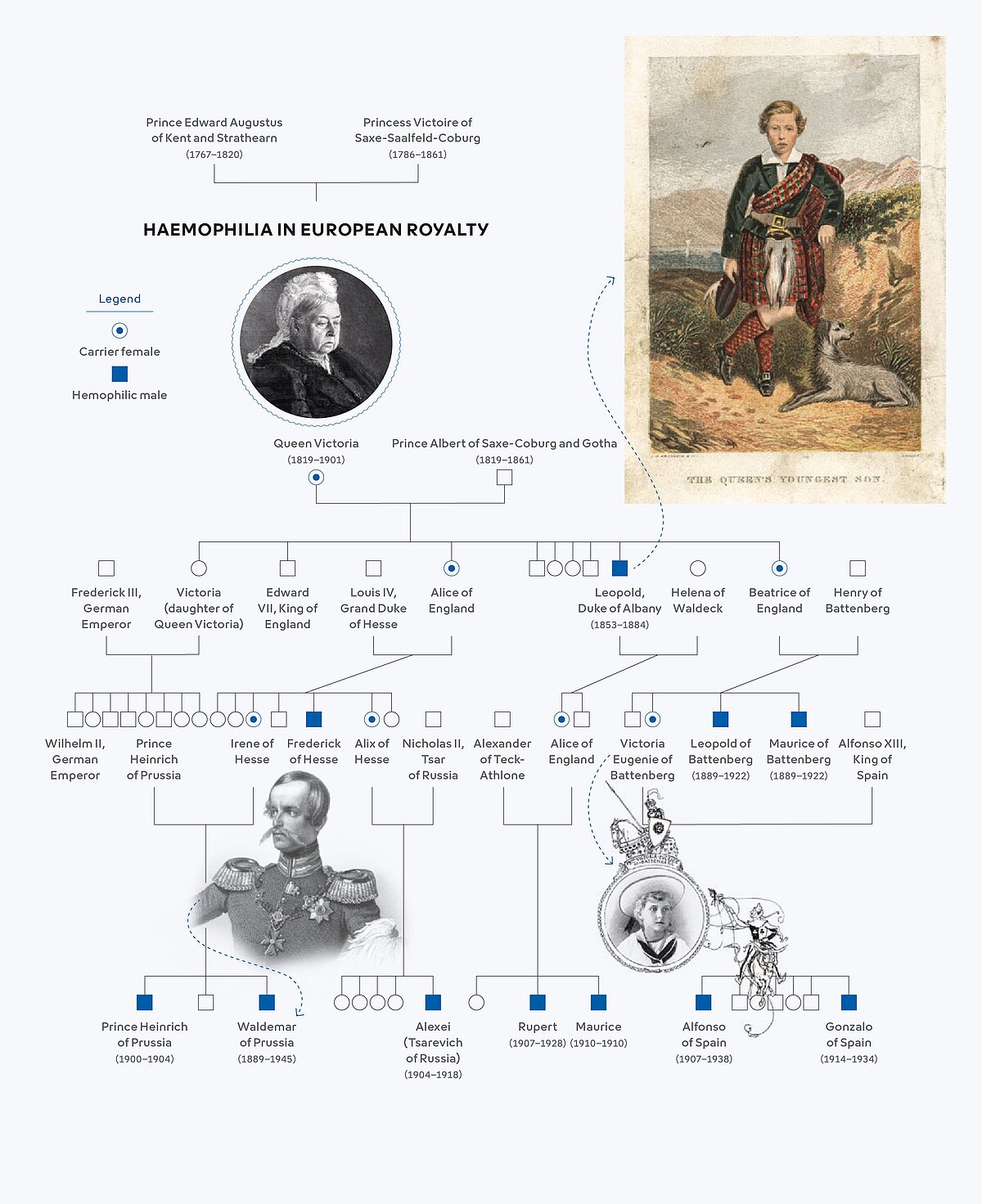

During the reign of Queen Victoria in the United Kingdom and Ireland (1819-1901), the most influential noble families were closely intertwined due to aristocratic intermarriage practices of the time. During the “Victorian era”, true to its namesake, Queen Victoria ruled for 64 years, with her 40 grandchildren and 88 great-grandchildren, earning her the nickname “Grandmother of Europe”. Of all people, she played the decisive role in the spread of haemophilia in her family. In her case, it was the rarer variant, haemophilia B, which is a deficiency of the blood clotting factor IX. One of her sons was a haemophiliac, while two daughters passed on the hereditary disease as carriers who were not affected by the disease themselves. Just within two generations, haemophilia spread from the United Kingdom to the ruling dynasties of Prussia, Spain and Russia.

In the spotlight

Haemophilia has been known and recognised since ancient times. In Jewish communities, unstoppable bleeding was discovered much earlier and more routinely than in Europe as a result of circumcision. The Jewish scholar Maimonides’ ideas on the inheritance of haemophilia date back as early as the 12th century.

In Christian-dominated Europe, however, haemophilia was not mentioned until the 16th century. The disease first came into the spotlight in Europe and North America at the beginning of the 19th century thanks to work of Dr John Conrad Otto, who also coined the term haemophiliac. There were families of haemophiliacs that resided in Kirchheim, Germany and Tenna, Switzerland who were thoroughly studied.

"Fritz has endless bruises again. He is pale and thin."

The first carrier

Haemophilia as a disease and also its hereditary principles were therefore already known by the middle of the 19th century when Queen Victoria gave birth to her daughter Alice in 1843, the first carrier of haemophilia among Victoria’s children. Research has not conclusively determined whether Queen Victoria herself or her father, Prince Edward Augustus of Kent and Strathearn, is considered to be the source of the haemophilia.

Like around a third of all haemophilia sufferers, it is possible that Victoria did not inherit the disease, but that a spontaneous change in her genes – a mutation of the X chromosome – was the trigger. This is generally supported by the fact that Victoria herself came from a famous noble family, and it can be assumed that a case of haemophilia in her family would have been recorded in writing.

However, it is also conceivable that the mutation occurred when Victoria’s father’s reproductive cells were formed. Studies have shown that the probability of a new mutation during sperm production increases with the father’s age. Since Victoria’s father was already 52 years old when she was born, he could also be a possible source.

The disease then developed in Victoria’s children based on the hereditary principles. In 1870, Victoria’s daughter Alice gave birth to her son Prince Friedrich of Hessen and passed the disease on to him. Recorded written entries, such as “Fritz has endless bruises again,” and “He is pale and thin from his illness,” describe his condition at the age of two. He died in an accident at the age of three.

The hereditary disease reached the House of Hohenzollern through Alice’s daughter Irene. Her two sons, Queen Victoria’s great-grandchildren, also inherited the disease. Born in 1900, Prince Heinrich of Prussia, a nephew of the German Emperor, died at the age of four after falling from a chair while playing. Such a fall or bruising can trigger internal bleeding in a person with haemophilia, which can be very dangerous or even life-threatening if not prevented or treated. Four-year-old Heinrich’s fall most likely caused fatal internal bleeding.

Helpless doctors and a miracle healer

Even the best doctors were still helpless in the battle against haemophilia until the beginning of the 20th century. The symptoms of the disease and the laws of inheritance had been researched, but there were no treatment options. Apart from applying compression bandages and prescribing bed rest, the doctors could not do anything. A noble and wealthy background did not provide any protection against unstoppable bleeding. Until 1940, the average life expectancy for haemophilia sufferers was around 15 years.

Victoria’s granddaughter Alix, who was also a carrier, brought haemophilia to the Romanov ruling dynasty in Russia. Alix married the Russian Tsar Nicholas II in 1894 and their only son Alexei was also a haemophiliac. There were numerous cases that described bleeding in his joints and the large muscle in his lower back. According to reports, the Tsar’s son came close to death several times.

In one story, Alexei was standing in the aisle of a railway carriage during a planned journey and looking out of the window. When the train came to a stop, he lightly bumped his face against the window. Moments later, blood gushed from his nose and a crowd of doctors struggled for hours in vain to stop the bleeding.

Even the best doctors were still helpless in the battle against haemophilia

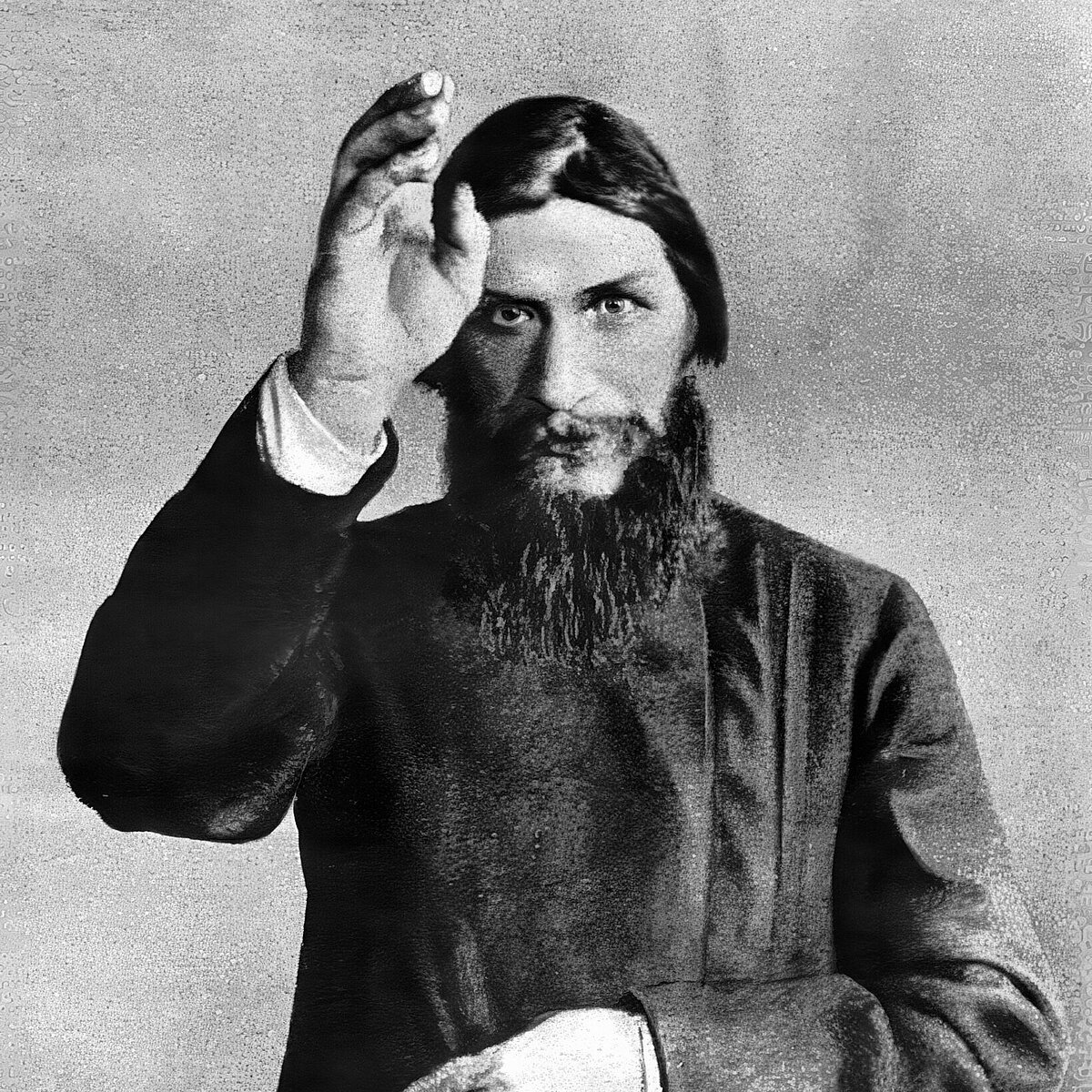

It is believed today that Alexei suffered from a severe form of haemophilia. The Tsar’s family tried to keep the disease a secret; after all, Alexei was the official heir to the throne. He wasn’t allowed to ride his bike or run around playing. Two servants always looked after him, even carrying him if necessary. In their desperation, the Tsar’s family turned to the already well-known and notorious Russian “miracle healer” Rasputin.

The major milestones in the treatment of haemophilia were to come later.

There are many contemporary accounts of how Rasputin stopped the Tsar’s son’s bleeding simply by persuasion, hypnosis, suggestion and eve from a distance. Taking today’s knowledge on the clotting disorder into context, one may perceive Rasputin to be an obvious charlatan in his treatment practices, but many respected doctors from St Petersburg at the time confirmed the healing powers of Rasputin, who was usually brought to the Tsar’s son via the back entrance unseen. He himself became an influential man because – as the legend goes – he was able to stop every bleeding episode that Alexei suffered from and thus gained the trust and gratitude of the Tsar and his wife. Despite this success, turbulent times followed. In the end, both Rasputin and Alexei, along with his family, were murdered.

Through the marriage of Queen Victoria’s granddaughter Victoria Eugénie to the Spanish King Alfonso XIII, haemophilia was also passed on to an heir of the Spanish throne: Alfonso of Spain, born in 1907. However, the Spanish king was forced to abdicate by a revolution in 1931 and Alfonso was not able to succeed him to the throne. He died in exile in America after a car accident.

The truth

The fact remains that the cases of haemophilia in the ruling dynasties had no political consequences, even if the circumstances invited such speculation. A mother with a defective X chromosome has a 50% probability of passing on the disease to her children. As fate would have it, those who suffered from the disease in the first two generations after Victoria were not at the forefront of politics and were not reigning monarchs. Things could have gone very differently; if Queen Victoria had passed the disease on to her first daughter, haemophilia might have been inherited by one of her sons, the German Emperor Wilhelm II.

Among Victoria’s great-grandchildren, however, there were two first-born heirs to the throne who had inherited the disease: the Russian Tsar’s son Alexei and the heir to the Spanish throne Alfonso. However, in the wake of the First World War and the revolutions at the beginning of the 20th century, the great monarchies in Europe had come to an end before either heir ascended the throne. Both cases of the disease, at the very least the severe form of haemophilia in Alexei, could have had far-reaching consequences due to their high-ranking positions of responsibility and influence.

Even though haemophilia was very well documented in the noble families and the symptoms of the disease and laws of inheritance had already been extensively studied, this did not result in any new medical findings. That was perhaps the fateful and tragic reality; wealth and connections could not protect the victims. The Russian Tsar’s family saw obscure and mysterious healing methods as their only path of escape.

The major milestones in the treatment of haemophilia were to come later. The first experiments with blood transfusions were performed around 1840, but blood groups were not discovered until 1900. Victoria’s great-grandson, Waldemar of Prussia (born in 1889), who had also inherited the disease, was able to live to the age of 56 with the help of the first blood transfusions. Today, modern treatments, such as extended half-life factor concentrates or factor VIII mimetics, allow haemophilia patients to not only survive for much longer, but also enjoy a life that is minimally impacted by the condition.

Despite all the tragedy for the nobility of the time, one thing can be said: The spread of haemophilia in the ruling dynasties in Europe in the 19th and early 20th centuries certainly ensured that haemophilia became widely recognised as a disease. It was later also referred to as the “disease of kings”.